Watch this video to learn about tornadoes! Click here to download this video (1920x1080, 139 MB, video/mp4).

Heavy, dark clouds hang low, dumping buckets of rain and hail. Suddenly, a twisting column of gray drops from the bottom of the cloud. For a while it hangs suspended in the sky. Then it extends to the ground. When it touches, it goes even darker as its ferocious whirling winds pick up dust, debris, and—if the windspeeds are fast enough—cows, cars, roofs, mobile homes, trees, and anything else not well-anchored in the ground.

A strong tornado can pick up massive objects like trucks and drop them many miles away.

What makes a cloud create one of these powerful assaults to Earth's surface? How is it that a violent whirlwind can form in a cloud and then reach to the ground and make splinters and chaos of everything in its path?

A bad year for Tornado Alley... and Alabama

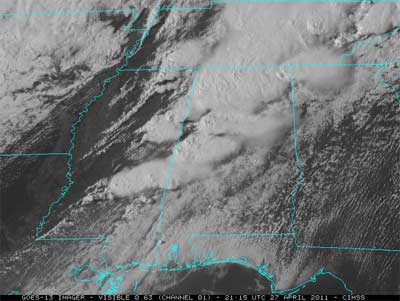

April 2011 set the U.S. record for the most tornadoes in any month.

On average, the U.S. gets about 1000 tornadoes each year. A ten-state area of the Midwest has been named "Tornado Alley" in recognition of its attractiveness to tornadoes. However, tornadoes can occur in any state. In 2011, Alabama was struck particularly hard, with tornadoes rated EF-5 (the most intense) on the Enhanced Fujita scale hitting Hacklesburg and Birmingham.

Imagery from GOES-13 enabled weather forecasters to foresee the trouble that was about to hit Alabama. Click image for animation.

With most weather events, even hurricanes, you know what to expect. The weather forecast will give you a few hours' warning and some idea of what is coming. This information is thanks partly to hard-working satellites that keep a constant eye on the weather.

However, predicting tornadoes precisely is a different story. One minute it's just raining or hailing, and the next minute the roof or even the whole house is gone. If you were lucky, you and your family had a few seconds to find some shelter where you would not be picked up by the violent winds or seriously injured by large chunks of flying debris.

Where do they come from?

Where do these violent and unpredictable storms come from? Why do they destroy some buildings, but leave others nearby untouched? And is there any way weather forecasters could give people right in their path a little more warning?

Certain conditions make tornadoes more likely. So, in that way, they are somewhat predictable. But no one ever knows when, where, how intense, and how many tornadoes a thunderstorm will create.

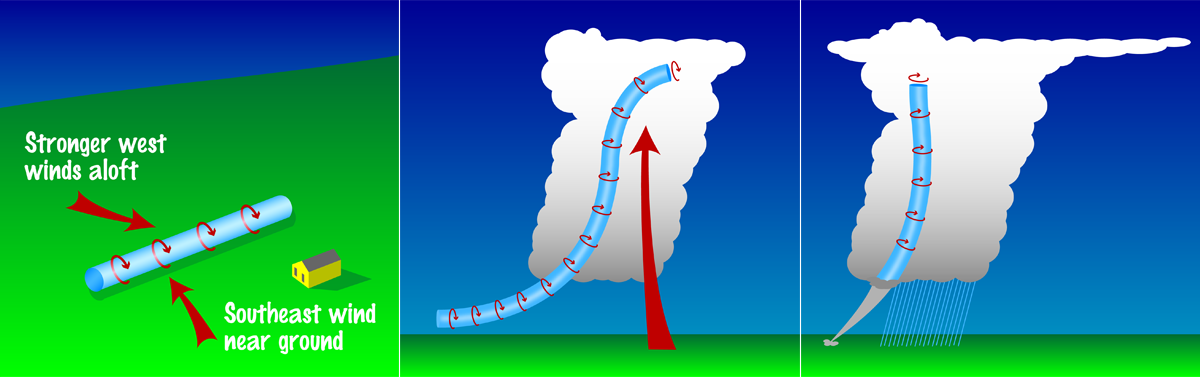

Conditions are ripe for tornadoes when the air becomes very unstable, with winds at different altitudes blowing in different directions or at different speeds—a condition called wind shear. The first result is a large thunderstorm.

Inside the huge thundercloud, warm and humid air is rising, while cool air is falling, along with rain or hail. All these conditions can result in rolling, spinning air currents inside the cloud. Although this spinning column of air starts out horizontal, it can easily go vertical and drop down out of the cloud. When it touches the ground, it's a tornado . . . and a big problem to anything in its path.

The winds inside the spinning column of some tornadoes are the fastest of any on Earth. They have been clocked at over 300 miles per hour! Sometimes the spinning column of air lifts off the ground, then touches down again some distance along its path. It seems all very willy-nilly and makes you wonder “why them and not us?” Or, just “why us?”

Comparing tornadoes

It's hard to measure the winds in a tornado directly. So they are evaluated by the amount of damage they do. Here is a scale meteorologists use to describe tornado intensity based on damage.

| ENHANCED FUJITA SCALE | |

| EF No. | 3-Second Gust (mph) |

| 0 | 65-85 |

| 1 | 86-110 |

| 2 | 111-135 |

| 3 | 136-165 |

| 4 | 166-200 |

| 5 | Over 200 |

Can we get more warning?

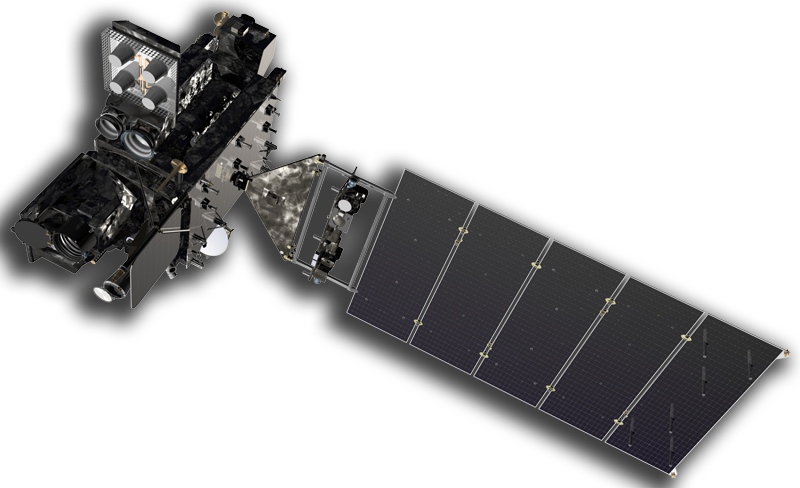

NOAA's GOES-R Series weather satellites do a better job than earlier satellites of identifying storms likely to produce tornadoes. These satellites can more quickly monitor the motion of clouds to identify a severe storm as soon as it develops. They are also better at understanding what's actually going on inside the cloud: what characteristics the cloud has that indicate a severe storm and how much lightning it produces. All these measurements affect how likely the cloud is to produce a tornado.

GOES-R series satellites will be better at seeing what's actually going on inside the cloud: how much lightning it produces, cloud top properties and the motion of the clouds. All these measurements affect how likely the cloud is to make tornadoes, and what kind of tornadoes it could produce.

GOES-16 imagery of a tornado-producing storm in southwest Iowa on June 28, 2017.

We can't prevent tornadoes, but the more warning we have, the more lives will be saved.